Based on personal experience, here's why I think NHS hospitals urgently need to modernize their IT architecture if they are to successfully adapt to variable operating models, meet exponential patient demand, and improve treatment options for women with breast cancer.

The National Health Service (NHS)

The UK is incredibly fortunate to have a National Health Service (NHS) that is the envy of many parts of the world. Established in 1948, care is free, and accessible by all, ensuring patients don’t suffer financial hardship due to ill health. It is a healthcare system we are incredibly proud of, sustained by more than 1.4 million hardworking men and women, with 1.5 million patient interactions every day. Through my work I have been privileged to work with a number of IT Teams across the NHS, who do an amazing job of keeping some incredibly complex systems running smoothly, delivering best-in-class patient care.

My breast cancer diagnosis

Never in a million years however did I think, during the course of my work, that I’d be sitting on the other side of the fence, in the role of ‘patient’, relying on the medical imaging technology I’d become so familiar with over the years, to confirm my own cancer diagnosis. In January of this year I found a lump, which was subsequently diagnosed as breast cancer. Following a recent single mastectomy, I want to not only thank the amazing NHS staff who have supported me on my journey - but also highlight some of the loopholes I observed during the course of my diagnosis and treatment. I share this not just from my own perspective as a patient, but also as a woman who’s spent 20 years working in tech as a guardian and champion of medical imaging applications.

Concerns for patient care

A lot has happened in the last few months. And I mean, a lot. I’m still on my treatment journey, and I don’t have immediate answers to what my next steps will be - whether I’ll need chemotherapy, or my other breast removed. But having spent so many nights reflecting on what was happening, I wanted to be candid with the medical imaging community, in the hope that it might prompt debate on how to close some of these loopholes - or indeed for others to reassure me that these problems are all being addressed behind the scenes!

To be clear, I cannot fault the NHS ‘machine’ once I was inside the system; the amazing nurses, doctors, and clinicians who treated me (and continue to support me). However, the lack of data integration and poor communication between departments (let alone between hospitals) has me not only worried but also angry about the lack of consideration apparently given to some of these issues. These technologies save lives. Every day. And for the reasons I’m going to highlight, my overarching concern is that we’re still not patient-centric enough to deliver the care they (and I) so desperately need.

Who else are we talking about?

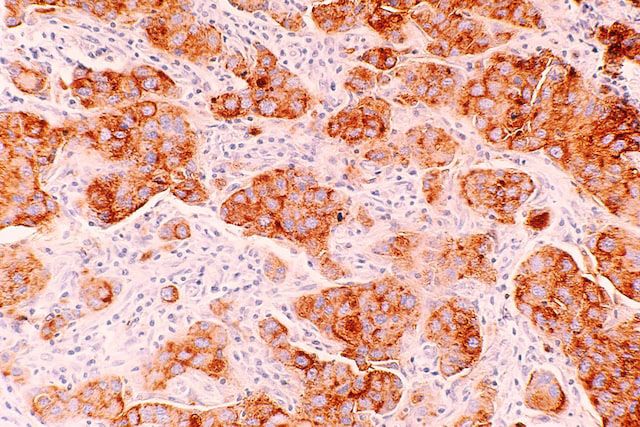

The number of new malignant cancer cases per year in the UK is 320,711 (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer), and 531 cases per 100,000 population. Of these, more than 55,230 men and women are diagnosed with breast cancer, with 61.3% of females attending breast cancer screening within the government target period of two weeks. The good news is that more than 75% of these people go on to survive breast cancer. Early diagnosis (and of course therefore medical imaging equipment) is crucial to setting patients on the right path to treatment and recovery. Medical imaging modalities for breast cancer typically include mammograms and MRIs - although for patients like me, ultrasounds and Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT) as well, for reasons I’ll explain.

And as one of those statistics, here’s my personal take on breast cancer diagnosis, treatment, and its implications for the future of medical imaging.

Inadequate modalities and processes for patients with pacemakers

I have a pacemaker; as do more than 500,000 other people in the UK. In the US, up to 3 million people are estimated to have one. Inevitably, (due to known limitations of mammograms for women with dense breasts) many women with suspected breast cancer receive an MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) to confirm their diagnosis. Nevertheless, for those of us with pacemakers at least, magnets and pacemakers aren’t a good mix. And there aren’t great screening alternatives for me and my messy band of pacemaker misfits.

I had to have an ultrasound, and then ultimately a Digital Breast Tomosynthesis to confirm how many lumps I had, how advanced they each were, and precisely where they were located, so that my surgical options could be determined. So my question is, surely for women with dense breast tissue (40% of women over 40) and pacemakers, there must be a better alternative than putting those women through three different scanning procedures at a time when every hour diagnosis is delayed is absolute torture? Surely the medical imaging equipment used should be different for women over 40 straight off the bat? And, if not, at least for women with pacemakers? While the beauty of the NHS system means women with suspected breast cancer get seen quickly, there needs to be more flexibility in the medical imaging procedures employed much earlier on, instead of requiring patients to jump through unnecessary hoops just because it’s part of a formal process that suits the majority.

Poor access to medical images

What totally floored me was not only the number of people involved in my diagnosis and treatment, but also the fact that none of my scans were accessible to others further down the line. The only information shared between clinicians was a few sentences of text the interpreter of each scan recorded in my notes, summarizing their professional opinion, before passing me on to the next person. I never saw the same person twice. While I respect that each individual is clearly extremely well qualified, surely human errors are less likely to occur if medical images can be viewed by more than one individual? Similarly, why not put a photo next to the patient’s scans to reduce interpretation errors? Even experienced clinicians are prone to errors, especially as work days become longer, and workloads increase.

Having worked with medical imaging applications for many years, I fully appreciate the size of some of these files (a breast MRI can be an average of ~300 MB of data storage per study), but these challenges can almost always be overcome. There are ways of integrating these files through resilient, secure and scalable architecture for the transfer, storage and retrieval of these images. And if an image cannot be shared between Departments within the same hospital, what hope do we have of sharing data across hospitals, with third parties, or between private and public sector facilities?

Admittedly, countries that have already been through the pain of introducing EHR systems have come a long way in addressing some of these challenges. In the US the government passed the HITECH ACT (Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health) as far back as 2009, actively encouraging hospitals to adopt EHR and Interoperability Programs. And the NHS is working to implement EHR as part of its Healthcare Support Network policy - although it has yet to make this a reality. However, true interoperability won’t just be solved by a single NHS EHR system. There are far broader ecosystems and applications that also need to be incorporated, with individual organizations continuing to opt for software that’s viable for their individual needs. So are open standards like FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) more likely to bring these disparate systems together? I know Apple certainly think so.

Public and private breast cancer treatment

In theory, private and NHS breast cancer treatment should be the same or very similar, although the tests necessary for diagnosis may be available faster when done privately. Through my own research, I found very limited data available to determine how many women receive breast cancer diagnosis or treatment privately in the UK every year, and even less information on how many women pass through the private and public sector through the course of their diagnosis or treatment - as is becoming increasingly common.

It used to be that patients had a choice between private healthcare (for those lucky enough to be able to afford it) or public (accessed through the NHS). Now however, it’s increasingly likely that patients are dipping in and out of the NHS to utilize private healthcare providers for specific parts of their diagnosis or treatment. Many patients do this electively to overcome long waiting times, and backlogs in the NHS. However, more and more, the government itself is seeking to outsource elements of patient care to the private sector.

For example, increasingly the NHS is doing deals with private firms to provide additional capacity for cancer care. This is totally understandable, while hospitals try to clear the backlog caused by the pandemic. But even without this, demand is only ever going to increase, so this must surely be a model we will see more of. Only if patient databases across these sites and systems can be shared, will patient care truly remain uncompromised. In order to receive the necessary tests and data to determine my treatment choices I had to hand deliver my medical records from private to public consultants and back again. Surely at a time when patients are extremely vulnerable, and perhaps not as forthright as me (!), the onus should not be on the patient to act as postman, or to relay complicated medical advice from one oncologist to another? I was asked to email notes several times, and to remember to tell the next person that X had been done, and Y couldn't be done. Why is that the patient's responsibility?

The importance of interoperability

I hope this doesn’t read as a diatribe against the NHS. As I said, the people who work there are all amazing - and I don’t just mean the clinicians. I have the greatest respect also for the Solutions Architects, IT Managers, and Engineers who work in the IT teams of large hospitals, grappling with significant challenges on a daily basis. Healthcare infrastructure is an incredibly complex beast, often funded by multiple stakeholders, and with different vested interests and agendas, resulting in disparate systems, complex, legacy IT, and outdated processes. This complexity is also the result of an incredibly fluid operating environment, which faces daily crises, which can afford little downtime (if any).

But my belief is that these interoperability challenges can be overcome, because I have seen it done, and in certain circumstances we have played a small part in this - both within the NHS, but also internationally. So my appeal is that we start to urgently tackle some of this head-on, in order to further advance patient care, and to uphold our conviction in the provision of ‘best-in-class’ healthcare.